There are days when sisterhood shows up not in speeches or declarations, but in simple acts of care. Today, on a Sabbath, I found myself at a spa with women who have, over the years, become more than colleagues. They have become sisters. We had decided, almost on a whim earlier this week, that we had neglected ourselves for far too long. A WhatsApp group was created, and when I jokingly asked, “Who is the sponsor? I’m very, very broke,” one of them responded: “Don’t worry, we will take care of it.” Another sister volunteered to cover my bill entirely and she surely did.

It felt spontaneous, yet divine. Only a few weeks ago, in conversation with church elders, I had lamented how long it had been since my last proper spa visit. I spoke of the toll economic hardships had taken, how both time and money had conspired against me, making such care feel impossible. I never imagined that God, who hears even our quietest laments, would provide through a caring sisterhood. What felt like a whim was, in truth, an answered prayer.

𝙒𝙝𝙚𝙣 𝙉𝙚𝙚𝙙𝙚𝙙 𝘾𝙖𝙧𝙚 𝙁𝙞𝙣𝙙𝙨 𝙔𝙤𝙪 𝘼𝙛𝙩𝙚𝙧 𝙔𝙚𝙖𝙧𝙨

The last time I had a proper spa visit was in Nepal three years ago, and before that in Nairobi, three months before Nepal’s. Since then, my life has been caught between village and town, between economic hardships and demanding schedules. A spa visit often felt like a luxury that belonged to another world. When I had time, I didn’t have money. When I had money, there was no time, or no spa in sight.

But today was different. I wasn’t just lying on a massage table for relaxation. Something unique happened. I reflected more deeply than I ever had during any past spa visit. I remembered my grandmother, my roots, and the generations of women who had always known the importance of such care.

𝙒𝙤𝙢𝙚𝙣 𝙃𝙖𝙫𝙚 𝘼𝙡𝙬𝙖𝙮𝙨 𝘽𝙪𝙞𝙡𝙩 𝙎𝙥𝙖𝙨 𝙤𝙛 𝙏𝙝𝙚𝙞𝙧 𝙊𝙬𝙣

As I lay there, my thoughts drifted to childhood memories of my late grandmother; Doruka in 2002. I once witnessed her receiving a massage not in a spa, but in the yard of our village home. Her co-wife (bother-in-law’s wife) had walked nearly 18 miles on foot carrying oil extracted from the African python. A mat was laid out behind the house, soap and oil were mixed, and the massage began. Grandma groaned as aching muscles found relief under careful hands. At the end, she thanked her co-wife profusely.

That was their spa with no scented candles, no background music, no white robes. Just sisterhood. Care rendered in the form and context they had.

It struck me today that spa culture is not foreign or wasteful, as some men (especially in my country) like to say. It has always been here, arranged differently, depending on resources and setting. Where money was scarce, women found other ways to minister to each other’s bodies. To dismiss it as indulgence is to erase a history of women’s care that is deeply embedded in our communities.

𝙎𝙞𝙨𝙩𝙚𝙧𝙝𝙤𝙤𝙙 𝙖𝙨 𝙖 𝘾𝙖𝙧𝙚 𝙀𝙘𝙤𝙣𝙤𝙢𝙮

Women have always understood something fundamental: survival and thriving require tending not only to the soul, but to the body. A proper bath, a rub, oils pressed into aching muscles; these were not luxuries but healing rituals. They were also acts of solidarity, where one woman said to another: “I see your pain, and I will help carry it for a while.”

Today’s spa experience, paid for by my sisters, mirrored the same dynamic. It wasn’t about luxury, but about a care economy that women build when systems around them fail. In a world where economic hardships and cultural dismissals push women to the margins, such acts of collective care remind us that sisterhood is wealth.

𝙎𝙖𝙗𝙗𝙖𝙩𝙝 𝙍𝙚𝙨𝙩, 𝙍𝙚𝙞𝙢𝙖𝙜𝙞𝙣𝙚𝙙

I had worried about missing church fellowship this Sabbath, so I attended mid-week prayers to remain spiritually grounded. Yet as the week wore on, I also felt an increasing need for deeper physical rest. I do daily exercise, at least 20 minutes without fail under normal circumstances but I knew deep down that a spa visit would be uniquely therapeutic, a way to truly fill my cup.

So instead of being in church today, I chose to tend to my body. I realized that healing my muscles and quieting my spirit was the rest I needed most at this time. This wasn’t about indulgence or income, it was about health, wholeness, and renewal. The Bible reminds us, “The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath” (Mark 2:27). What better way to honor the essence of Sabbath than to rest body and soul in the fellowship of sisters?

The quietness of the spa, the healing touch, the laughter we shared, it was fellowship in its own right. It was rest redefined, rooted not in ritual alone, but in the wholeness that God intended when He commanded His children to rest.

𝙍𝙚𝙩𝙝𝙞𝙣𝙠𝙞𝙣𝙜 𝙈𝙖𝙨𝙘𝙪𝙡𝙞𝙣𝙞𝙩𝙮 𝙖𝙣𝙙 𝘾𝙖𝙧𝙚

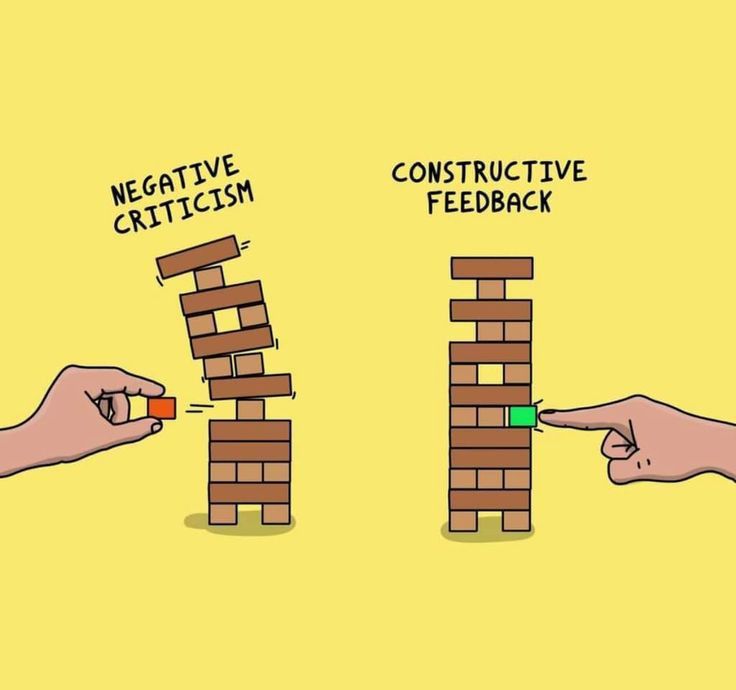

Today’s experience also reminds me of another truth: my grandfather knew his brother’s wife was coming to massage his own wife, and he respected it. He understood its importance. That quiet acceptance stands in stark contrast to the dismissive attitudes I see among many men today, who scoff at spa experiences for women as wasteful. Perhaps they do not realize that their grandmothers and great-grandmothers had their own versions of spas, long before there was money in circulation. To belittle such practices is not wisdom; it is ignorance of one’s own cultural heritage.

𝙏𝙝𝙚 𝙏𝙖𝙠𝙚𝙖𝙬𝙖𝙮: 𝙎𝙞𝙨𝙩𝙚𝙧𝙝𝙤𝙤𝙙 𝙞𝙨 𝙎𝙪𝙧𝙫𝙞𝙫𝙖𝙡

Today, as I enjoyed the care of my sisters, I realized we were not just pampering ourselves. We were continuing a tradition of women holding each other up, of creating systems of care where none exist, of affirming that our bodies too are worthy of attention.

I walked out of the spa carrying not just relaxation, but resolve. I will work hard to afford regular spa visits without shame. I will seek a partner who does not see caring for the body as frivolous. And I will cherish the sisterhood that reminds me, sometimes through simple acts, that I am seen, carried, and loved.

Because in the end, a sisterhood of care is not just about massages or baths. It is about women saying to each other: “you deserve ease, you deserve relief, you deserve joy.”

And that is something worth passing from one generation to the next.